Guilty Until Proven Innocent

In theory, pretrial detainees are protected by certain rights. Is this the case in practice?

6/21/20253 min read

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

The Eighth Amendment states:

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

While the Eighth Amendment protection does not apply to defendants charged in state courts, its place in the Constitution of our country should serve as a guiding light. The Supreme Court may not have explicitly ruled that the excessive bail clause applies in state cases, but it is the prevailing legal understanding.

“In the courts, civil rights bail litigation hinges on questions of federal and state constitutional interpretation. When is bail “excessive” within the meaning of federal and state excessive-bail clauses?” (Harvard Law Review)

The judicial system faces a difficult decision in meting out the appropriate denial of liberties to criminal suspects. Legally, bail is determined based on the seriousness of the crime, the defendant’s ties to the community, the flight risk posed by the defendant, and the danger posed by the defendant to the community. These are weighed against the rights of the defendant to prepare for their trial in the liberty of their own home and community.

In my husband’s case in particular, my experience was that his “ties to the community” were grossly overlooked in determining his bail. Chris grew up in Los Angeles surrounded by his close knit family. We live in a house passed down to Chris from his grandparents, and jointly run a small, solvent business supplying produce (microgreens, to be specific) to local restaurants. We are getting ready to have our first baby in August 2025. We are firmly set in our domestic ways, with our garden, our chickens and our small home gym. I have collected more than a dozen letters of reference from family, friends and employers vouching for Chris’s character.

Rights, Denied

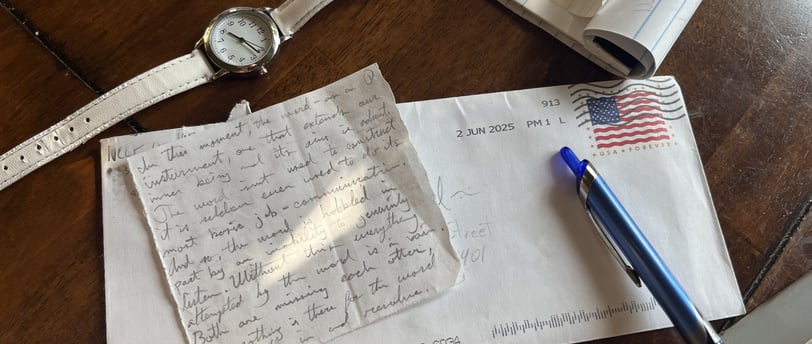

One of the primary difficulties for my husband during these months, and one of the challenges of pretrial detention often cited in bail reform studies, is that incarceration means “denying the defendant the ability to assist with his or her own defense”. (National Institute of Corrections)

This is problematic on numerous levels:

1. No Legal Literature

No legal literature is available to him, making it impossible for him to research even his most basic rights. Law libraries were largely reduced or eliminated in jails after the Supreme Court ruled during Lewis vs. Casey in 1996 that “Prisoners have a constitutional right to access the courts, but this is not violated when a prison lacks legal research facilities or legal assistance unless prisoners have been substantially harmed by these deficiencies.” (Lewis vs. Casey)

Based on my husband’s own experience speaking with other inmates, the percentage of detainees with the drive and literacy to research their case by reading dense, legal writing is very small. Given the oft-cited liberal ideals of “reform” or “rehabilitation”, it is interesting that so-called “correctional facilities” do not provide this particular learning opportunity for those detainees motivated enough to read law literature. Chris, who completed a Master’s program in education, is highly motivated to invest in attaining any information that may assist in his return to his wife and family.

2. No Communication

Due to the monitoring and recording of phone calls and visits, Chris is isolated from each progression or development in his own case until his attorney is able to go to visit him. This often means that I, as his advocate and the person in direct communication with the relevant parties, know far more than he does on a given day about his own case. I am unable to communicate any of this information to him, because our phone calls and visits are recorded and therefore not viable ways of communicating sensitive information.

Pretrial detainees have constitutional rights, notably Fifth and Sixth amendment rights. Unfortunately, this does not include “the related right to communicate without disclosure of those communications to the Prosecution.” (CHALLENGING PROSECUTORIAL USE OF A PRETRIAL DETAINEE’S ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS)

In addition to precluding the detainee from assisting with his case, this is an immense strain on faraway relatives who are only able to communicate via phone.

3. No Certainty

Isolation from the evolution of his case via the previous two factors has secondary consequences, namely the effect on both Chris’s mental health and my own. The uncertainty that each day brings aggravates his inability to face the best or worst outcomes from any given development and leads to anxiety and depression. This in turn is distressing for myself and his family as we support him from the outside. Not only that, but as husband and wife we are isolated from preparing for the possible outcomes together.

Punishment Before Conviction

I believe the punishment should fit the crime. What I do not believe is that the punishment should be premature. Pretrial detention may be warranted in many cases (in my husband’s case, I do not believe this based on his character and his deep community ties), but in theory pretrial detainees are still protected by certain rights. In practice I assert that my husband has no rights at all that are discernible from a convicted prisoner. It is my opinion that this betrays the American principle of “innocent until proven guilty.”

Chris and I remind each other daily, that no one can take away our God-given rights to think deeply, pray often and hope for a better future.